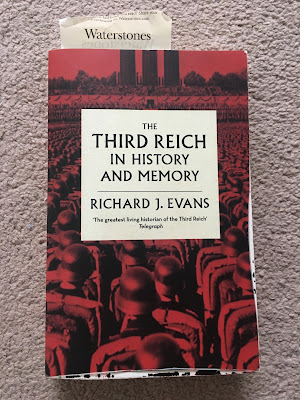

After wallowing in a bit of degree nostalgia with Richard J Evans, I was attracted to this book by the fact it was set in 1970s East Germany. I'd been fascinated by the GDR and the Stasi at university and this seemed an intriguing backdrop for a detective story. The central character, Karin Müller, is a police chief tasked with investigating the case of a grisly murder under the prying eyes of the Stasi, the infamous secret police.

Fittingly, there's more than meets the eye about the case and pretty much all of the characters we come across. Young captures the paranoia and corruption of the East German state well and it all serves to keep you guessing. All of the main characters have their own agenda and we see their back stories slowly peeled back, mirroring the progress of the case itself. It's refreshing to see the focus on 'real' people too - this is a Cold War thriller that isn't all about spies.

Through Müller we also see a different at the GDR. She's someone who doesn't yearn to escape to the west - she's sympathetic to the ideals of the socialist state and is appalled by the perceived excesses of the 'other Germany'. This makes her character all the more interesting for me. It's often difficult to understand how people in authoritarian regimes thought - and why they 'go along' with them - Müller helps us to see this. Her outlook doesn't make for a rose-tinted view of the GDR, but it does offer a richer understanding of the way real people acted and thought. Hopefully it will encourage people to delve further into the history of this short-lived but fascinating regime.

It's perhaps no surprise that the book is pretty grim too. I'm not sure anyone has a happy ending - and many characters are forced to make dark choices as events unfold. Just as we think Irma - a child we first find locked up in an institution for 'wayward' children - is going to get a positive future, for example, we learn that the price of her freedom is to spy on her mother for the Stasi. Informing on friends, family and neighbours was a macabre feature of the East German state and her story brings this to the fore powerfully.

We learn much of Irma's journey through first-person chapters which are interspersed throughout the narrative. It's an interesting writing device, and helps to build up the sense of mystery as the case develops.

Perhaps it's a little convenient that Klaus Jäger - the Stasi puppet master pulling the strings for much of the book - just fills in Müller with some of the missing details at the end to bring us up to speed but that's definitely forgivable and does explain away why some of the steps in the investigation feel a little coincidental.

All in all, Young weaves a complex web of intrigue over an atmospheric backdrop with Stasi Child. It's a riveting read and you can't help but be impressed by the quality on offer for this debut novel. Young tackles child abuse, corruption, authoritarianism, sexual abuse and relationships for good measure. He's also produced a set of three-dimensional characters and a detective story with a difference. I'm certainly looking forward to catching up on how he puts all of these puzzle pieces together in the next two Müller stories.